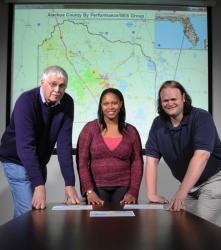

From left: Harry Daniels, a professor of counselor education, Dia Harden, a 2010 doctoral graduate (who participated in UF’s original “geo-demographic” study), and Eric Thompson, who received his doctorate this summer. (File photo)

As researchers across the country continue the search for early indicators of academic failure and dropouts, University of Florida education researchers are paying particularly close attention to warning signs predicting reading test scores.

Eric Thompson, a summer doctoral graduate in counselor education at UF’s College of Education, recently completed his dissertation research in which he dissected the causes of a reading achievement gap found among Alachua County students in third through 10th grades.

According to Thompson, the cause of low reading achievement may be rooted in how vulnerable a student has been to stressful circumstances in life, including a low socioeconomic level, minority status, and even low birth weight, which affect academic performance.

One of Thompson’s most significant findings is a striking difference in students’ achievement based on their socioeconomic status.

“Students living in low socioeconomic environments are more likely to encounter more risk factors and experience fewer supports,” Thompson said.

Although this research finding may not surprise some, Thompson said, he and his co-primary investigator Harry Daniels, a professor of counselor education, were able to uncover and describe exactly why such performance gaps occur.

Their studies showed that the least affluent students scored about 300 points less than their more affluent peers on the FCAT reading exam. Thompson also discovered that most affluent groups started with very high scores in the third grade, while the least affluent students started very low and stayed low throughout their schooling.

Low socioeconomic level was primarily determined by looking at each student’s family and community lifestyles based on spending patterns, credit card data and other related information.

However, Thompson’s research showed that students with a low socioeconomic level have also experienced other stressful life circumstances. Compared to students with a middle- to a high-socioeconomic level, the least affluent students were born at a lower birth weight; had parents who were younger and “potentially less mature” when the students were born; had parents with a lower level of education and a higher rate of unemployment; and are currently enrolled in schools with a higher percentage of students with free-and-reduced lunch and a larger population of minority students.

“It would appear from the onset that these students are at more risk for poor academic performance than those in the more affluent group,” Thompson said.

For his doctoral research, Thompson studied students’ reading scores between 2004 and 2011 and tracked trends based on four variables: each student’s biological qualities like gestational age and ethnicity, characteristics about each student’s family including parents’ education, the student’s school demographics, and the lifestyles of those in the student’s community. Thompson calls this the “individual-family-school-community model.”

“You have growth and maturation in the biological domain, including genetics and personality, and the social domain, which includes family, school, community,” Thompson said. “Within this intersection, you have risk and protective factors that relate to stress. The cumulative effect of stressors like poverty, family life and peer stress accumulates through time and can inhibit learning.”

The study also showed that not only did these individual, family, school and community characteristics differ among socioeconomic groups, but their influence on academic risk also differed. For example, minority status and the presence of minority students in their school did not affect affluent students’ performance. Thompson said that students living in a low-socioeconomic environment may receive fewer social and academic supports.

Thompson’s recent research is a follow-up of a 2010 “geo-demographics” study by a UF team that documented a profound correlation between home location, family lifestyles and students’ achievement on state standardized tests.

“While school improvement and teaching quality are vital, we are demonstrating that the most important factor in student learning may be the children’s lifestyle and the early learning opportunities they receive at home,” Daniels said.

Thompson and Daniels hope their findings shed light on the increasing need to tailor classroom and counseling activities so each student’s individual needs are being met.

“It would be irresponsible to treat every child the exact same way because every student comes from a different background and experience,” Thompson said. “We need to ask ourselves, ‘How do we help students develop a lifestyle conducive to academic success? How can we adjust the delivery of education to meet the needs of students from diverse backgrounds?’”

CONTACTS

SOURCE: Eric Thompson, doctoral graduate in counselor education from the UF College of Education, 352-328-9571, erict56@ufl.edu

SOURCE: Harry Daniels, professor of counselor education at the UF College of Education, 352-273-4321, harryd@coe.ufl.edu

WRITER: Alexa Lopez, UF College of Education, 352-273-4137, aklopez@coe.ufl.edu