NSF-funded study looks at how African American girls are steered away from science and math

Are you a “math person” or a “word person?”

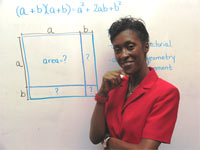

Pringle

Ask almost anyone that question, and they can give you an answer. But how did each of us decide we belong with the math whizzes or the budding novelists? How much of this is our own decision, and how much is forced on us by teachers and parents? And what roles do race and gender play in all of this?

These questions – particularly the last one – are the focus of a new study by three professors at the University of Florida’s College of Education. Funded by a $439,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, the study will look into the ways African-American girls are steered – and learn to steer themselves – away from science, mathematics and other technical subjects.

West-Olatunji

“If you ask an African-American girl in middle school to draw a picture of a scientist, chances are she’ll draw a white man with a long coat and a beard,” said Associate Professor Rose Pringle, a science educator who is leading the study. “Somewhere along the line we have lost too many of these children, and they are not being made aware that they can be successful in the sciences.”

It’s no secret that women in the sciences were once a rarity – and that American culture pushed girls, in subtle and not-so-subtle ways, away from the lab and toward the home. A whole generation of teachers has worked to create a gender-neutral environment in the math and science classroom, and there is evidence these efforts are working. The gender gap in enrollment in upper-level science and math courses is closing. African American girls, however, have mostly been left behind by those gains.

Adams

Pringle and her colleagues, Associate Professor Thomasenia Adams and Assistant Professor Cirecie West-Olatunji, have spent the past year trying to find out why. They’ve interviewed African-American girls in the crucial middle grades to find out why so many bright young science students choose to go no farther than the basics in math and science.

The collaborating researchers found that the girls in the pilot study did not, by and large, see themselves as future scientists, and they adopted that attitude largely because the people around them didn’t see them as scientists either. What’s more, the girls were well aware that they were being pushed in a certain direction.

The researchers say counselors and teachers send out subtle – but very clear — messages about their expectations. For instance, when a black student expresses an interest in higher education, a counselor might suggest community college, rather than a four year college.

“Educators are constantly asking, how do we win their hearts and minds, how do we get these kids interested in science,” West-Olatunji said. “Yet, in practice, it seems that counselors and teachers are still playing a gate-keeping role.”

The problem doesn’t start or stop in the classroom, the researchers say. After all, students spend most of their time outside the classroom, in a world that sends kids a million little messages about gender and race. For the most part, those messages aren’t telling black girls they should be scientists. In fact, the researchers say, even the girls’ teachers may doubt their own role in the scientific and quantitative world.

“We’re not laying the blame on teachers,” Adams said. “We ought to ask ourselves: does the teacher in the science classroom even perceive herself as a scientist?”

The NSF grant will allow the researchers to spend three additional years in North Central Florida schools, surveying parents, observing teachers and counselors in action, and looking for those crucial moments when adults send messages about their expectations for their students. They will also talk with students and analyze how those students internalize the message they’re getting from the people around them.

The grant comes as the NSF and other national organizations are searching for new ways to encourage students of all backgrounds to enter the sciences, technological fields and mathematics – sometimes known as the STEM disciplines. In recent years, increasing numbers of college-bound students seem to have turned away from STEM majors and toward other fields, and many educators fear a coming brain drain in the hard sciences.

Long before those concerns arose, however, diversity was a problem in STEM fields.

“For African Americans, and especially girls, the crisis is not coming, it’s already here,” said Pringle.