From Cuban Refugee to Distinguished Educator

Gerardo González’s story shows ‘education is the most powerful weapon’

On Feb. 9, 1962, an 11-year-old boy, his parents and younger sister landed in Miami from Cuba.

He didn’t understand English, and his working-class family was broke, having escaped Cuban dictator Fidel Castro’s regime with few possessions; for spending money, his father had smuggled out two bottles of Cuban rum, which he sold for $5.

The boy was Gerardo González, who would become one of the nation’s most prominent leaders of a school of education and rank among America’s most influential Hispanics. His career trajectory — from Cuban refugee to a distinguished career in higher education at the University of Florida and beyond — may not seem implausible in a country accustomed to stories of immigrants making good. Except for one thing: Gerardo was a slacker.

Struggling to make it in their adopted homeland, his parents relocated every year or two — to Pittsburgh to New Jersey and back to Miami — in search of better jobs and living conditions. Yet, Gerardo was a spectacular underachiever, ever mindful of being humiliated and temporarily suspended at his first U.S. school by an assistant principal for asking another student to translate words into Spanish.

Gerardo Gonzalez (far right) and his family in Cuba, circa 1956

“It seemed as if God, Himself, had written the words in the sky: Why don’t you go to college? Me? College?”

— Gerardo Gonzalez, former UF College of Education professor, department chair, and interim dean, and dean emeritus at Indiana University

His father’s hands

To motivate Gerardo to study hard, his father showed him his beaten-up hands, which had become scarred and stained from a lifetime working as an auto mechanic. “Look! You need to get an education so your hands don’t look like this.”

Assigned vocational classes, Gerardo worked afternoons in a clothing store and dreamed of managing his own shop one day; but when the economy tanked he was let go. “I was little more than a high-school dropout,” Gonzalez writes in a soon-to-be-published memoir, “not motivated to study in any way.”

What happened next seems utterly obvious now but for Gerardo it appeared nothing short of a divine revelation. A friend simply asked, “Why don’t you go to college?”

“It all sounds so simple to me today. But back then, when my future had suddenly disappeared, it seemed as if God, Himself, had written the words in the sky: Why don’t you go to college? Me? College?”

Yes, you, Gerardo.

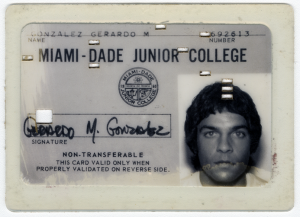

Figuring he had nothing to lose, Gerardo began taking remedial classes at Miami Dade Junior College, which had an open-door admissions policy, and he qualified for federal financial aid designed to help Cuban immigrants pay for higher education. Unsure what major to choose, he went to a career counseling office, took an aptitude test, and found that he was motivated not by money but by helping others. He chose psychology as a major and soon discovered a latent love for learning, a strong intellectual curiosity and, after he gained English language skills, a growing confidence that he could succeed in academia if he worked hard, cultivated mentors and pursued his passion for helping others.

“What made me so sure that if I worked hard I’d succeed? The image of my father’s hands, soaked in grease, and marked by a lifetime of toil,” Gerardo says. “I didn’t see myself as especially intelligent or talented. But a liberal arts education awoke in me a thirst for knowledge and lifelong learning. When I failed, I tried to learn from my mistakes. With each new insight, each new understanding, I grew more motivated.”

Gerardo says his decision to walk into the admission’s office of Miami Dade Junior College changed his life forever.

“I didn’t see myself as especially intelligent or talented. But a liberal arts education awoke in me a thirst for knowledge and lifelong learning. When I failed, I tried to learn from my mistakes.”

Success at UF

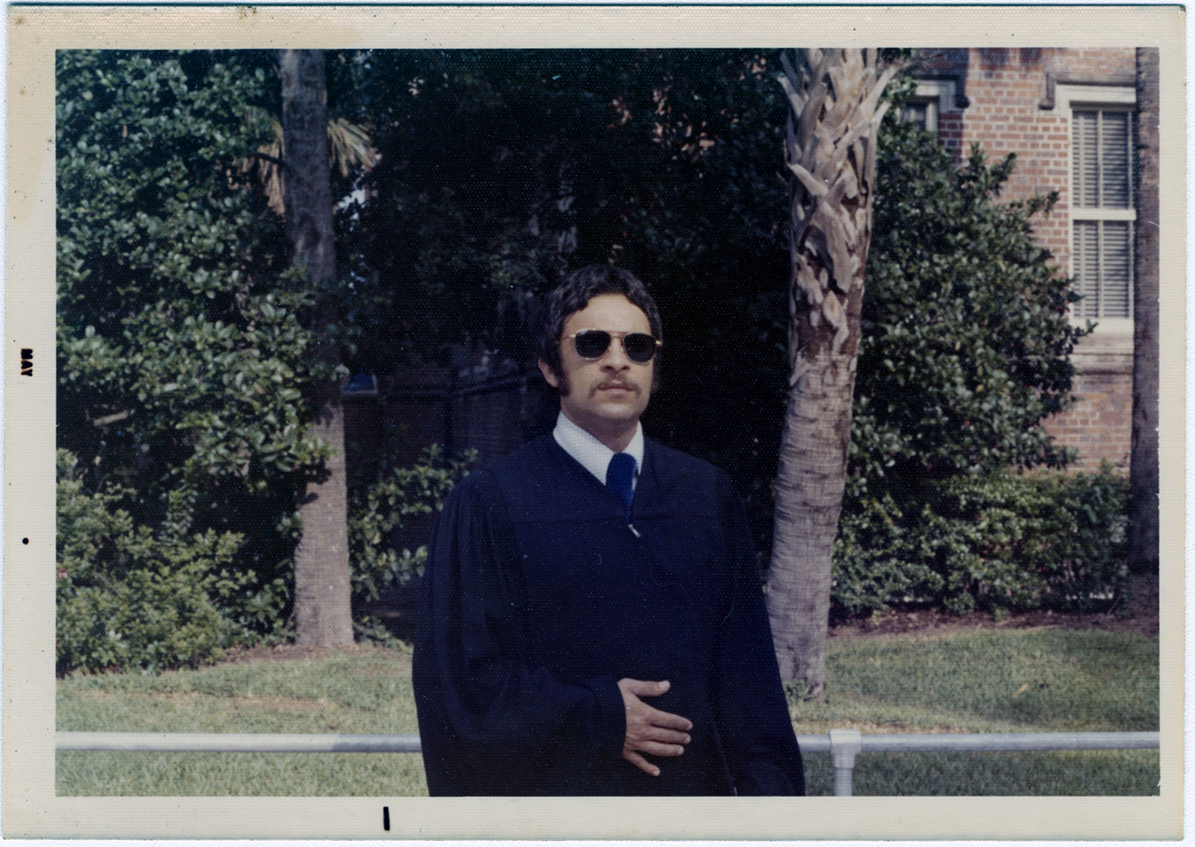

In 1972, he came to the University of Florida in Gainesville, where he would earn three degrees (bachelor’s in psychology, master’s in counselor education and a Ph.D. in counseling and student personnel services). His research focused on promoting health and preventing alcohol abuse among college students, an interest that had been sparked by witnessing close friends ravaged by alcohol and drugs. In time, Gerardo became known for his advocacy on behalf of disadvantaged students, his expertise on alcohol and drug education issues, and his outstanding administration skills.

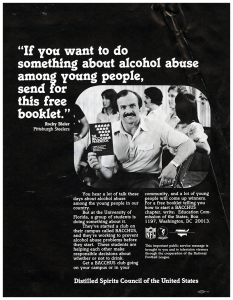

One of his earliest achievements came in 1975 at UF, when he founded BACCHUS (Boost Alcohol Consciousness Concerning the Health of University Students), named after the god of wine, which became one of the nation’s first campus-based alcohol awareness and prevention organizations. Under his decade-long leadership, the nonprofit group expanded to 260 campus chapters in 47 states and Canada, and helped start a national conversation about drinking on campus and transformed the way colleges responded to the problem. “Thanks to his efforts, BACCHUS has become one of the most influential alcohol-education abuse-prevention programs in the country,” The Chronicle of Higher Education reported in 1986 when he stepped down to become a faculty member in UF’s counselor education department.

In the ensuing years, Gerardo was tapped for a series of more prominent roles, including as director of the University of Florida Campus Alcohol and Drug Resource Center and assistant dean for student services. He was selected chair of the College of Education’s department of counselor education and then associate dean for administration and finance. Finally, in 2000, he was named interim dean, a stepping-stone to becoming the college’s permanent dean.

Instead, it led to one of Gerardo’s most difficult career decisions. Almost simultaneously, another institution, the School of Education at Indiana University, offered him the job of its dean. Gerardo chose IU, in part because he wanted to experience another institutional setting and community after spending 28 years in Gainesville at UF.

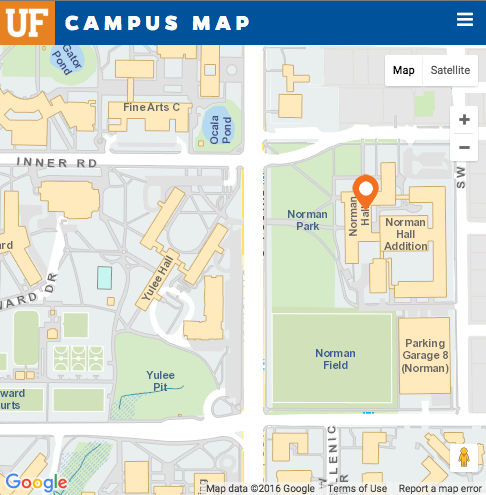

Gerardo Gonzalez is shown on campus in 1973 on the day he received a bachelor’s in psychology, the first of three degrees he earned from the University of Florida.

Rocky Bleier, a star NFL running back in the 1970s, appeared in print ads for BACCHUS, the campus-based alcohol awareness support group Gonzalez founded while at the University of Florida.

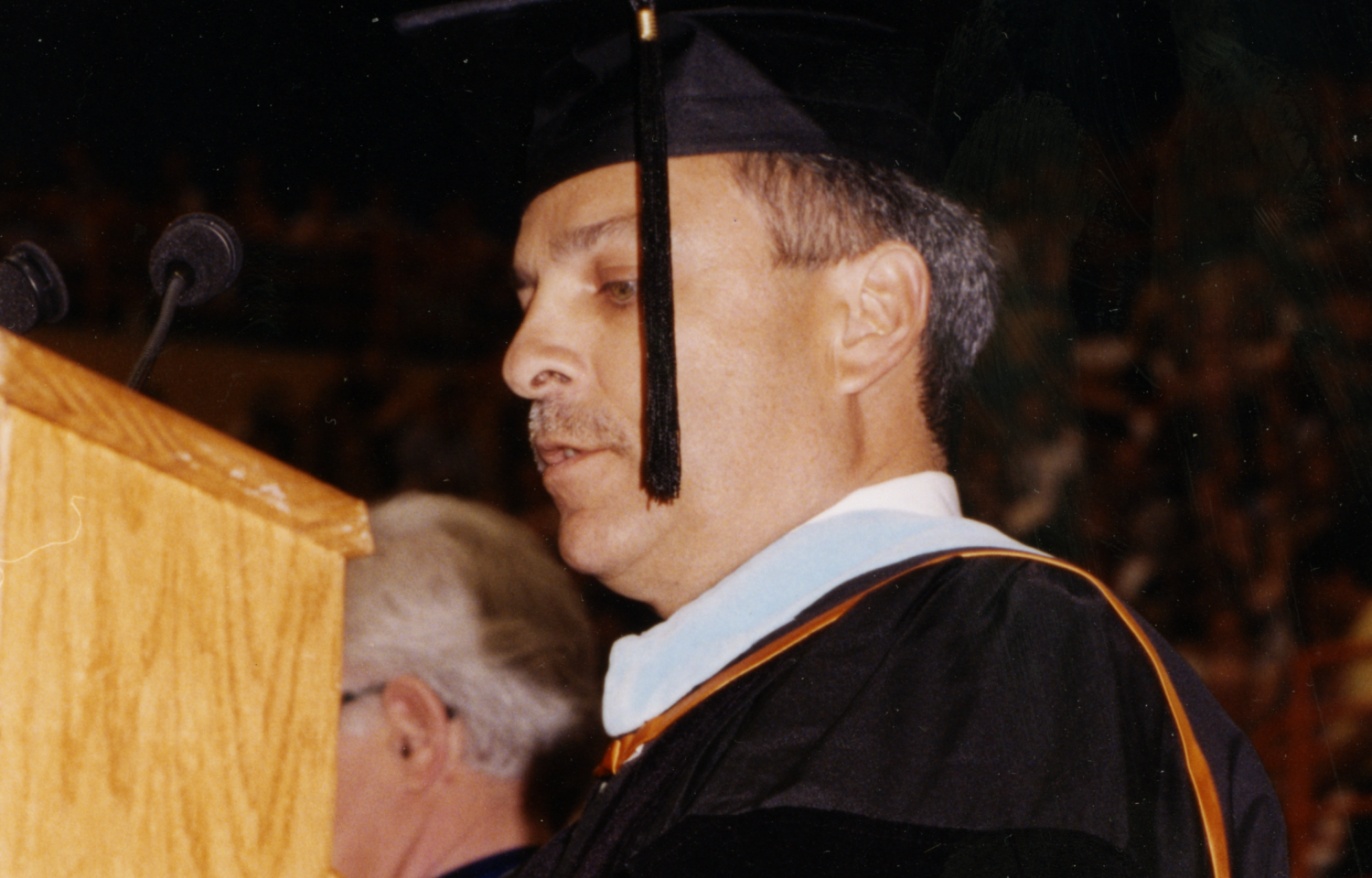

Named interim dean of the College of Education in 2000, Gonzalez presented graduates with their diplomas.

Fearless education advocate

In Bloomington, Indiana, Gerardo served as dean for 15 years, making his deanship one of the nation’s longest at a public school of education. Among his accomplishments was leading the creation of its first online doctorate program and recruiting a crop of diverse, high-quality faculty members. The defining factor of his deanship was his successful opposition to proposed reforms of Indiana teacher preparation and education policies, reforms Gerardo felt would damage K-12 education and teacher training, and he feared spread nationally.

As a result of his advocacy for enlightened educational programs, he gained a reputation as a fearless education activist and he spoke frequently to national and international groups about the need for policies that best serve all learners, as well as Hispanic education concerns. In 2012, Hispanic Business named him one of the 50 most influential Hispanics in the United States.

“I hope my experiences can help support new immigrants, refugees and other life voyagers struggling to fit in,” he says.

“My story shows that in the United States as in other democratic countries, education is still the great equalizer.”

Full circle

The final chapter of Gerardo’s career started soon after he retired as dean on June 30, 2015 when IU selected him as its educational ambassador to his old homeland, Cuba. He joined the first delegation of U.S. higher-education leaders to visit the island since then-President Barack Obama re-established diplomatic relations and reopened the U.S. embassy in Havana in July 2015.

The trip was a homecoming for Gerardo, returning to his old province of Villa Clara, near the small town of Placetas where he grew up. This time, he was there not to escape a repressive regime but to help rebuild relations. He negotiated the first post-thaw institutional agreement between IU and a Cuban university, a partnership to collaborate on educational initiatives, such as on study-abroad opportunities and research exchanges.

He had come full circle, ending up where he had started.

These days, Gerardo frequently spends time at his condo in Crescent Beach. Reflecting on his career, he credits many things for his success: perseverance, finding community, seeking mentors, pursuing your passion, trusting serendipity and remembering your roots.

“My story shows that in the United States as in other democratic countries, education is still the great equalizer,” he says. “It is the solution to the greatest and most intractable problems facing the world today, tomorrow and in the foreseeable future. As Nelson Mandela famously said, ‘Education is the most powerful weapon we can use to change the world.’”

Gonzalez attended a UF ceremony honoring College of Education deans (from left) Roderick J. McDavis, David C. Smith, Gerardo, and Ben F. Nelms.

Program Spotlight

More about our top-ranked Counselor Education program.

Giving Back

Learn about the ways you can contribute to our mission.